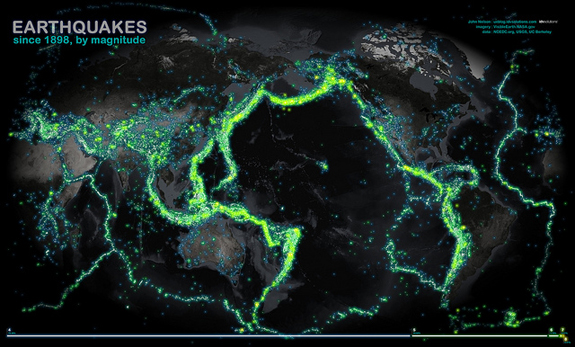

Maggie Koerth-Baker, Boing Boing's science editor, captions:

This map of all the world's recorded earthquakes between 1898 and 2003 is stunning. As you might expect, it also creates a brilliant outline of the plates of the Earth's crust—especially the infamous "Ring of Fire" around the Pacific Plate.She continues:

One of the theories explaining intraplate earthquakes is based off the fact that the tectonic plates we know today have not been constant throughout Earth's history. Some of the places that are now "intraplate" were once right along fault lines. Others are at spots where continents began—and then failed—to split apart. All these things might leave behind spots of "weak" rock that's more prone to upheaval than the strong, intraplate rock around it. Studies in the 1990s found that 49% of all intraplate earthquakes happen near places like this. Of course, that leaves 51% of the shaking still unexplained.New Zealand had yet another quake experience last night. (You can see, looking at the map, that for we New Zealanders earthquakes are not an unfamiliar phenomenon.) In any case, this one was big. The Civil Defense Minister used last night's tremor to remind us that all of New Zealand is earthquake prone. "A major earthquake could happen anywhere and people need to know what to do when that happens. Understanding a hazard helps in any emergency situation."

If there was an amusing part of last night's post-quake period, it was the flurry of Facebook statuses and tweets that could be seen as little as ten seconds after — perhaps even before — the earthquake had ended. As one of my fine Facebook comrades quite rightly pointed out, in previous generations during an earthquake people would have rushed immediately to the nearest doorway, now they run to their laptops. I weighed in: "Okay, everybody: enough quake wittering. Back to your Graham Norton." It's funny, though: a community's collective experience appears to have been reduced to earthquakes and television.